Interview with Nicolien van der Keur

July 2018

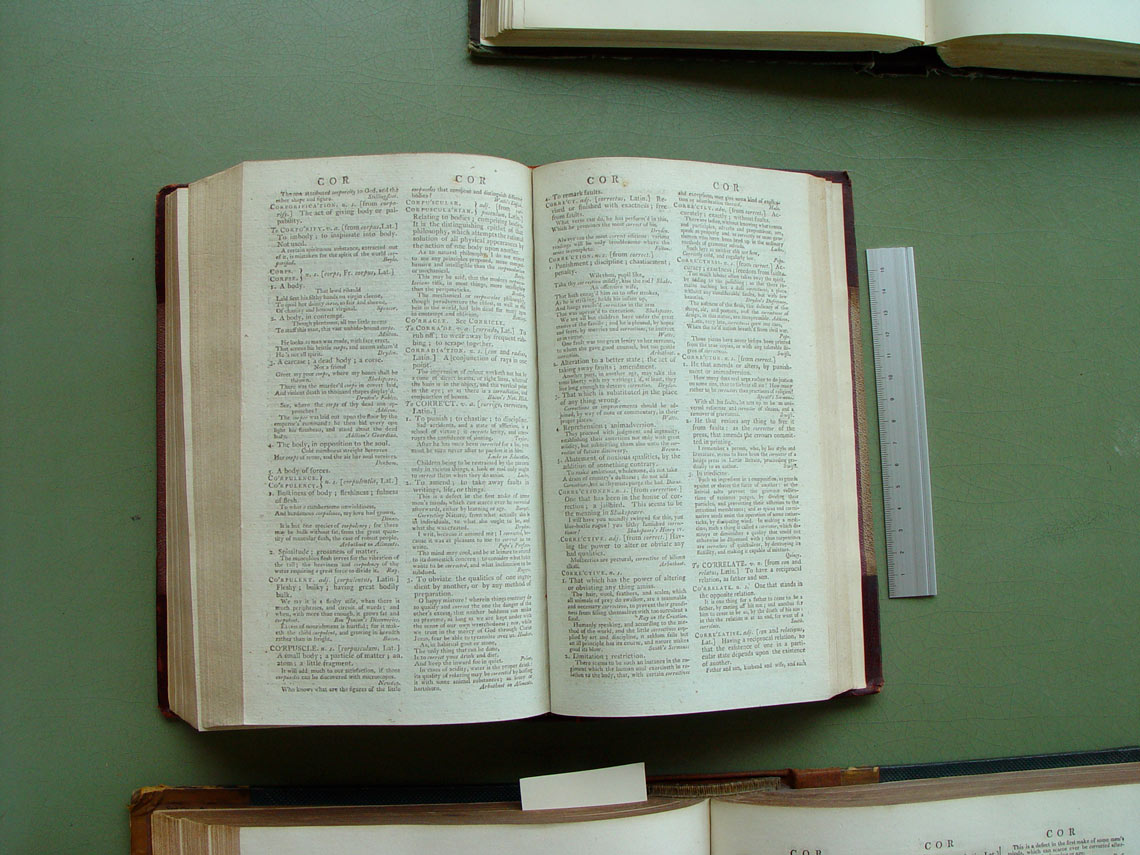

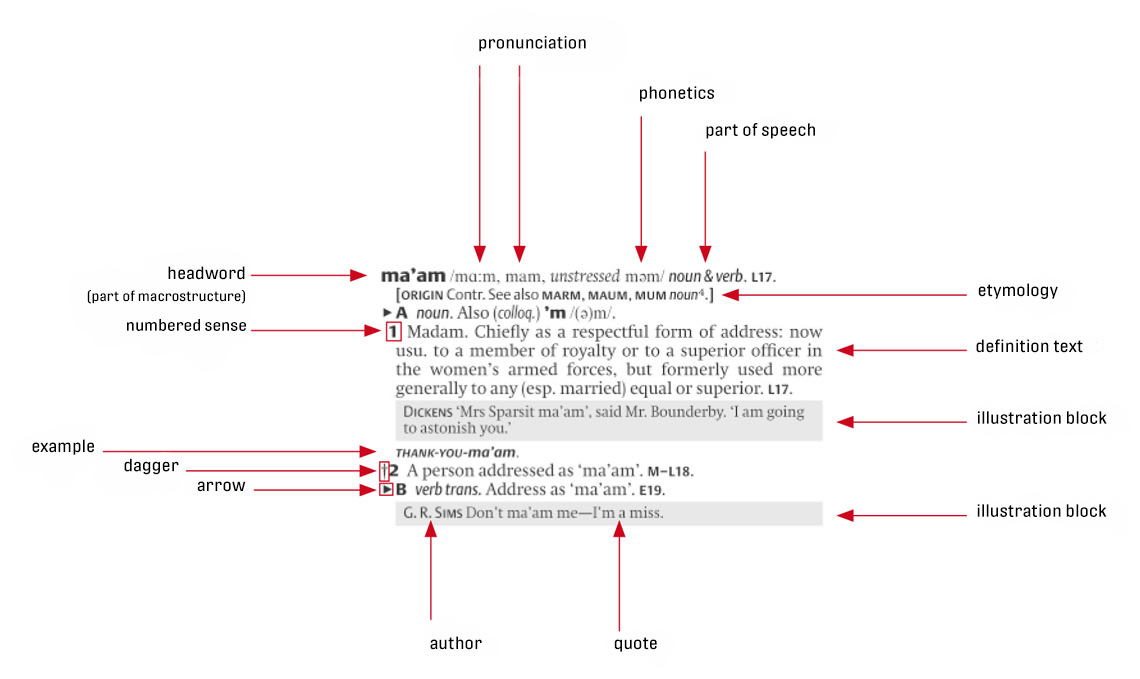

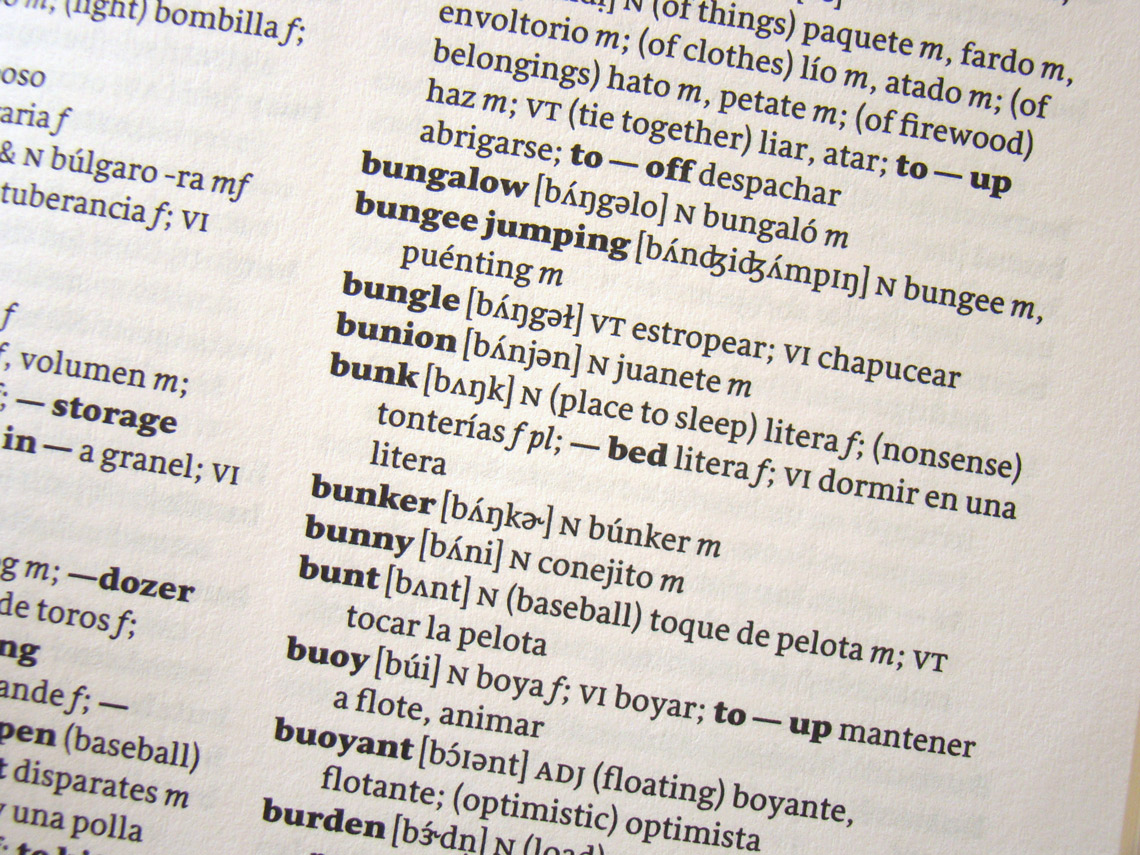

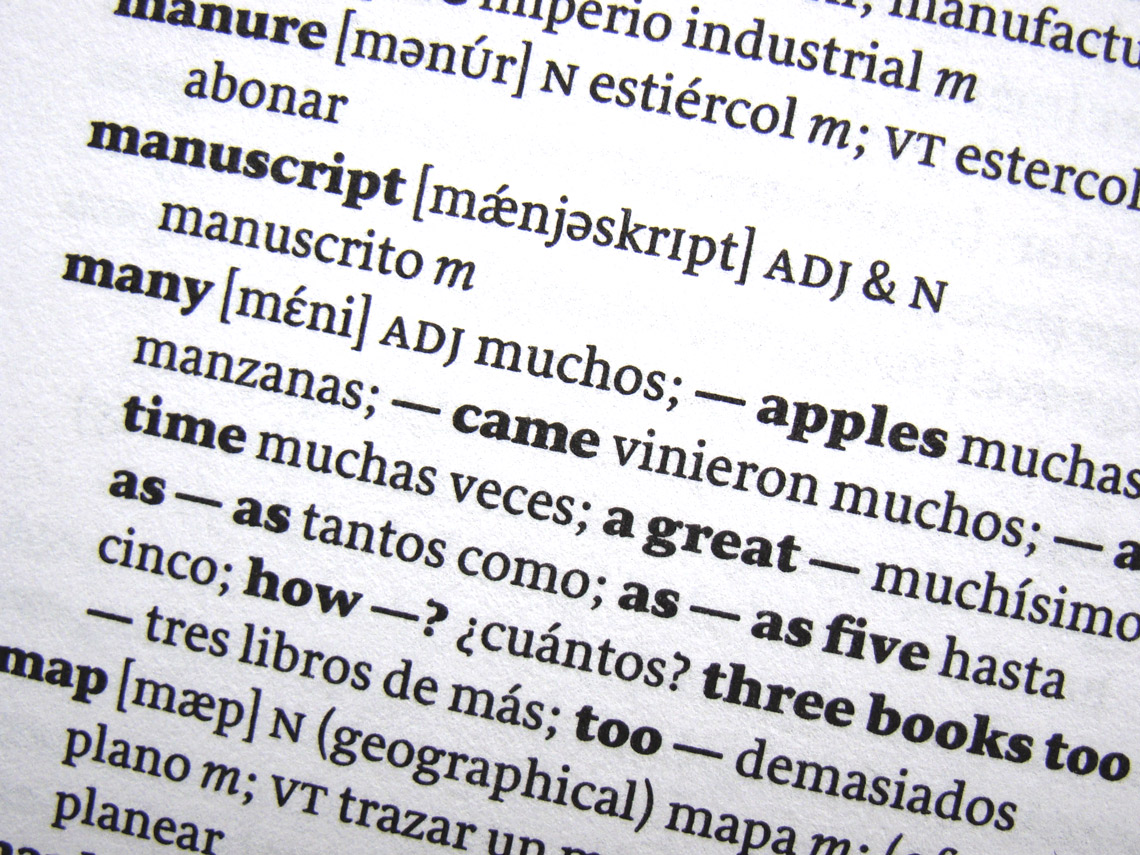

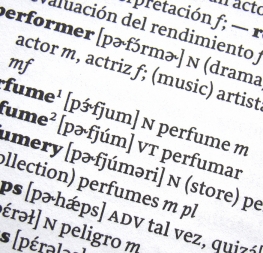

Acquiring an advanced degree often means moving somewhere new. But not many embark on this kind of adventure once they are well established. Nicolien van der Keur is just such a rare individual, risking safety for the opportunity to better herself and improve in her practice. Over a digital cup of coffee we talked with Nicolien about her history of making, her transition to font student then professional type designer, and her future plans. After reading this interview we hope you’ll read your home dictionary with a more critical eye and greater respect as well.