Interdisciplinary and collaborative research

Very early while conceptualising this project, we realised the importance of seeing the issue of handwriting education in primary schools from diverse viewpoints. We didn’t want to be limited by what may come easily to us as visual designers, but instead cast our nets widely and learn from a range of sources and fields.

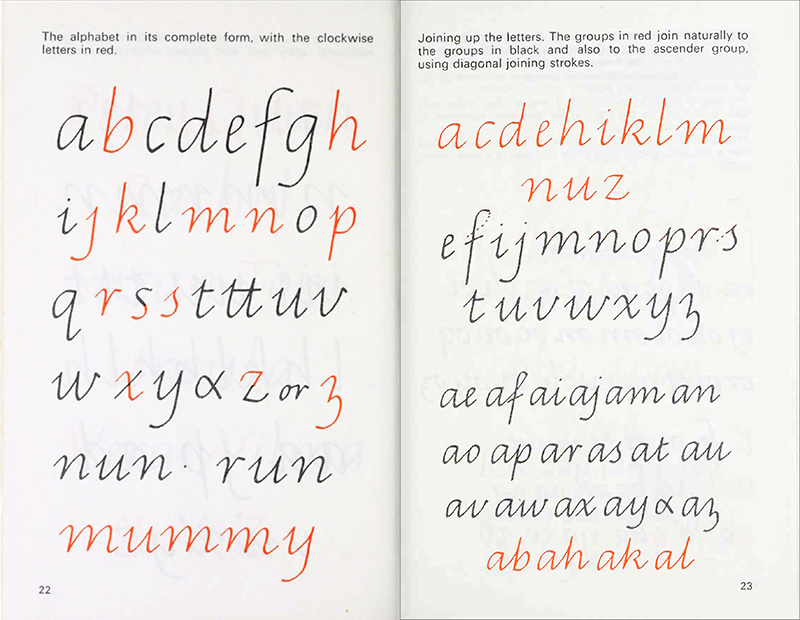

As a result, our research has taken us from poring over legislative documents to investigating historical threads; examining curricula and syllabi to surveying teaching materials; reading academic publications to reviewing marketing information from educational publishers; and examining typefaces as well as lettered samples. All of this desk research has been complemented by interviews with teachers, parents, educationists, administrators, and designers who have helped us contextualise our learnings with their real-world experiences.

The ins and outs of teaching

The logistics of how handwriting is taught also offers a study in contrast. Take, for instance, the age at which children are expected to write in fluent handwriting according to national curricular requirements. It is 7–8 years old in New Zealand, but 12–13 years in neighbouring Australia — a difference of half a decade!

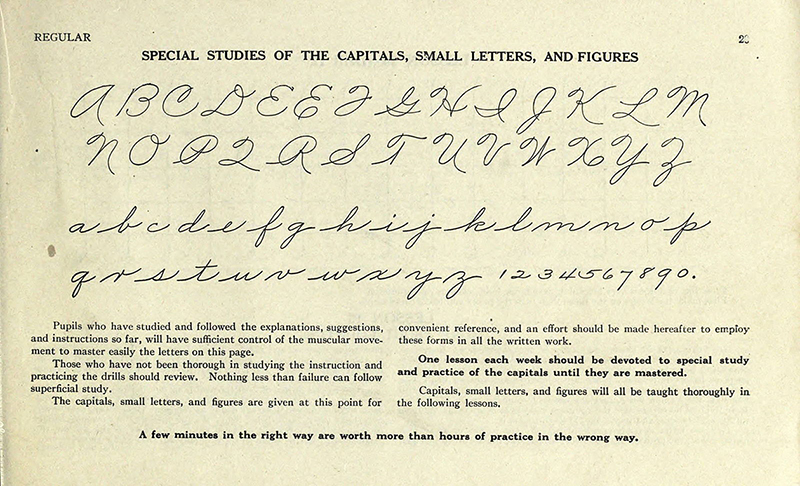

Similarly, the degree to which national governments are involved in preparing and recommending handwriting models changes from country to country. As recently as 2013, the French Ministry of Education introduced new models of handwriting called Modèles d'Écriture Scolaire A et B to reform handwriting teaching. Compare that to the United States, where models developed and marketed by private companies, such as Zaner-Bloser and Getty-Dubay Italic, rule the roost.